“The history of Africa will remain suspended in air and cannot be written correctly until African historians connect it with the history of Egypt.” – Cheikh Anta Diop

Death rituals and mummies continued as I made my way from the 18th dynasty into the common era and the Romans. When I got to the museum a little after opening, it was empty and hushed in the back galleries. Absolute heaven. I looked at more mummies and surreptitiously trailed after a guide and eavesdropped as she explained the rationale behind preparing the body for burial. The heart stayed in, as a “feather light heart” smoothed the way to the afterlife. The brains were removed from the nose (they didn’t understand what its function was – likely would have revered it had they known), but it, and the rest of the organs were removed. The body was salted heavily, dried, and wrapped firmly in linen. It was covered in amulets, the more the better, for the journey to the underworld. I also learned about why every statue of a king was posed the same way: right fist is a vow to fight for the country; left foot forward is a power stance. They are all exactly the same.

I meandered into a gallery with a stunning display of gold sandals and faience (glazed ceramic) jewelry. Four ladies were standing there, chattering: “This is pretty boring, but I’m loving the bangles thing!” “Do you think they only had four toes?” “What a cutie patootie!” “Hey, I’m wearing turquoise!” They were having fun, but I moved along – not my desired soundtrack.

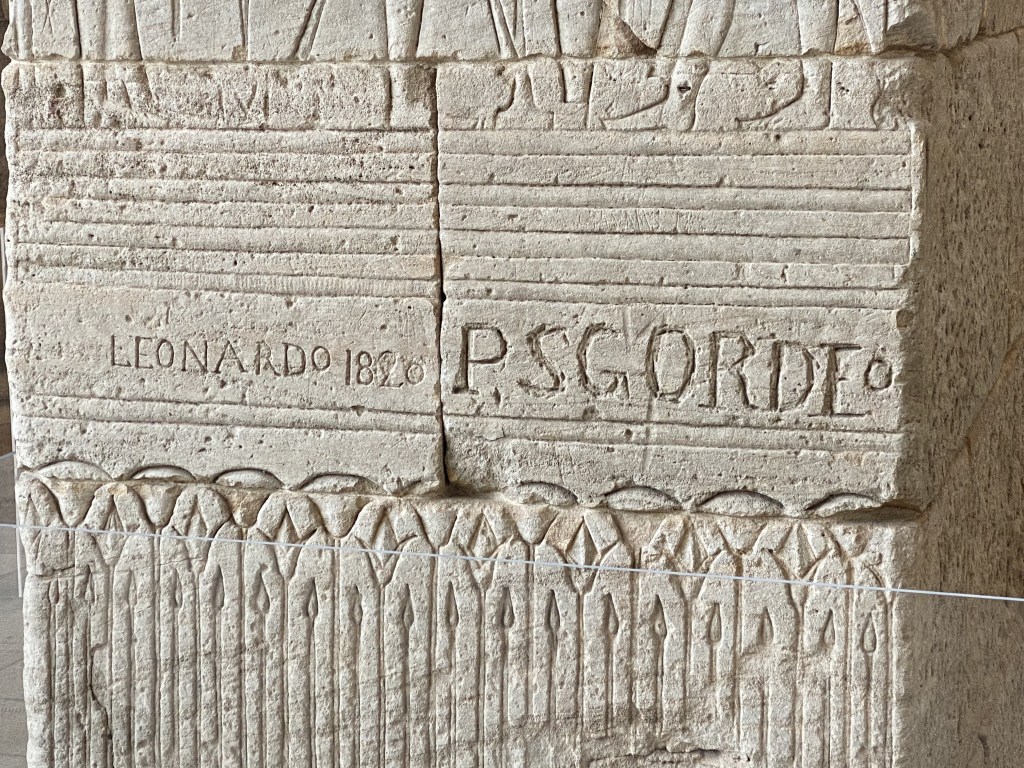

The Temple of Dendur is a respite – a large, cool space, with a water moat, papyrus growing in it. Moving forward, I will head there from anyplace in the museum whenever I need a break as it is bigger and less crowded than the rooftop garden. Its back story is crazy. It was built in 10 AD, turned into a Christian church around 600 and by the 19th century was a hot destination for seekers and artists. At the end of that century, a dam was built that periodically flooded, and after a new dam was built later, many monuments flooded permanently. Egypt and Sudan enlisted UNESCO to save the monuments, which they did. As way to say thank you to America’s help, Egypt gave the temple to Lyndon B. Johnson. (Thanks, bro, here, have this temple.) LBJ then donated it to the Met. They shipped it over bit by bit, rebuilt it, then built the gallery around it. One of the weirdest parts is all the graffiti. 19th century explorers, when they came upon the monument, carved their names on it. Whyyyyyyy? I mean, yeah, of course they did. It is covered with exquisite carvings – all those men’s names! – jk – birds of all kinds, and rays of the sun with hands on the ends of each ray blessing the king, and people burning incense, making offerings to Isis. Ad of course, gorgeous hieroglyphics on everything.

Also in the temple area, the four statues of Sekhmet the lion headed goddess of war, were arresting – stopped me in my tracks. She was known for violence and fierce protection, so was considered a goddess of healing when appeased. Because of her, physicians were considered priests for their ability to heal.

In the center of Egypt, in the Met, lies a room called The African Origin of Civilization. A timeline circles the room, starting with the engraved tablets found in southern Africa from 80,000 years ago to African Grammy winners in the 21st century. (Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, a book I have taught many times, is also on the timeline.) The exhibit itself is a repudiation of the way in which African art has been displayed in isolation. As though there is no overlap with it and anything else. As though there were blank leaps from 80,000 BC to ancient Egyptian sculpture to African art’s resurgence in the early twentieth century. The Egyptologist, scientist, activist, and historian, Cheikh Anta Diop (1923-1986) made it his life’s work to challenge Africa’s place in history and recenter it as the source of modern humanity. The exhibit is set up with ancient Egyptian pieces and icons paired with 19th and 20th century pieces around a theme (female agency, male power, commemorating beauty, visualizing hierarchy) as a tribute to Diop’s 1974 book The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality? I appreciate the Met telling on itself with this exhibit, and that they are completely re-doing their African art exhibit, not reopening until 2025. I spent a good long time in there – it gave me a lot to think about, in particular the ways that people in power get to influence what is valued. I know I am writing something plainly obvious, but something about the way the 19th century “explorers” pissed all over, I mean carved their names into, an Egyptian temple, and that it took this long for African nation states to achieve independence frustrates me. This exhibit gave me a little hope, though.